Almost one in five workers in the UK today was born abroad.[i] Migrants fill as many as 25% of health and care jobs, and 22% of all jobs in communication and IT.[ii] This is not just an outcome of mobilities past. Industry leaders project that migrant labour is also critical to the delivery of strategic government objectives, including building more housing for a generation of Britons who do not yet own a home,[iii] caring for an increasingly older population,[iv] and sustaining growth.

Yet despite this vital contribution to the UK, the future of work migration looks daunting. In the five years since the UK officially left the European Union (EU), the government has replaced a system of largely free movement with an archaic system of sponsorship where migrant workers’ mobility is to a large degree controlled by their employers. Reports of labour exploitation soared, as thousands of unscrupulous bosses[v] used their power over visas to deceive, overwork, underpay, and threaten migrants who complained with deportation. But it is the government’s response to this exploitation that casts the biggest shadow over the future of migrant workers – and with it, over the future of progressive politics in the UK. In this article, I reflect on how we got here and what is at stake.

The end of free movement and the rise of sponsored work visas

The UK’s exit from the European Union on 31 December 2020 opened a new chapter in the history of labour migration. Just days before the end of free movement, on Christmas Eve, a triumphant Boris Johnson declared that the UK had “taken back control of laws and our destiny […] every jot and tittle of our regulation.”[vi] But words alone have never filled vacancies, and as businesses continued to need migrant labour, the Home Office had to come up with a system that would meet business requirements, while retaining the image of strict border control. This is how we came to “the points based system” – more accurately known as the system of employer-sponsored visas.

From January 2021, businesses were allowed to recruit foreign nationals, provided they obtained a licence from the Home Office, and asked the department to issue sufficient Certificates of Sponsorship (COSs) to meet their recruitment needs. Employers would grant a COS from their batch to every foreign national they wanted to hire, and the COS enabled migrants, in turn, to obtain the essential points to obtain a work visa. All visas under this system were strictly tied to the sponsoring employers. If employment ended, migrants officially had just 60 days to find another sponsor, or risked sliding into irregularity.[vii] The tie of sponsorship could only cease if, after 5 years of continuous employment, migrants applied for Indefinite Leave to Remain. In many ways, this was similar to the migration system applied to non-EU nationals before Brexit – only this time it was wider, it grew faster, and employers had to jump through fewer hoops.

More businesses get a licence to sponsor

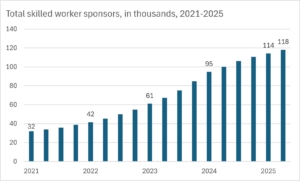

On the surface, sponsorship was working. Within the first couple of years, the Home Office had licensed almost 30,000 new businesses (Fig 1). This almost doubled the overall number of employers entrusted to sponsor migrant workers long-term.

Figure 1 – Total number of employers with a Tier 2 licence to sponsor skilled workers. Source: Transparency in Migration statistics, last updated Q2 2025.

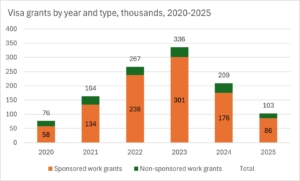

In that same period, as many as 661,000 sponsored work visas were issued to main applicants and their dependents (Fig 2), in sectors like care, which took the lion’s share of international recruitment, but also hospitality and IT. It did not take long, however, for the cracks in the system to appear – and reports of labour exploitation soared.

Figure 2- Entry clearance visas issued to main applicants and dependants. Source: Home Office statistics, last updated Q2 2025.

The first reports of workers exploited by visa sponsors

Suddenly, then irreversibly, around the start of 2023, the Work Rights Centre, the employment rights charity I run, started getting a new and worrying pattern of enquiries.[viii] People from India, Bangladesh, then gradually from Ghana, Nigeria and Zimbabwe, who had come to the UK hoping to work in adult social care, but also other sectors, contacted the charity to report an unusual pattern of financial and labour exploitation.

In almost every case, the story followed the same arc. Migrants had sold land, quit good jobs and borrowed money to pay eye-watering fees to agents who pretended they could place them with Home Office-approved employers. The employers were licensed, and the visas they opened access to were valid. Upon arrival, however, the work promised never materialised. The workers who dared to speak up were often threatened with deportation, usually, but also with violence. Meanwhile, they were stuck on a visa that was so controlled it neither permitted them to access public funds nor to take up other full-time work. Too indebted to return to their countries of origin, most of our clients were getting by on casual work, with loans, support from friends or food banks, hoping only that one day they would find a fairer employer to sponsor a new work visa.

Calls for reform of the sponsorship system intensify

Within a year, the story of how the Home Office had built a system ripe for exploitation featured in every major news outlet.[ix] By that point, the Work Rights Centre wasn’t just supporting victims of scams. We were also bringing tribunal cases for victims of forced labour who had been severely overworked, underpaid, and threatened if they dared to blow the whistle. Our reports were joined by other charities, MPs, the Independent Chief Inspector for Borders and Immigration,[x] the Public Accounts Committee,[xi] and the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner.[xii] Together, we left the government in no doubt: sponsorship is a work migration system that dangerously deepens the power imbalance between workers and employers, and is in urgent need for reform.

The policy solutions, we at the Work Rights Centre argued, were evident. The ambitious option would be to end sponsorship, a system that is more reminiscent of Tudor vagrancy laws than is suited to today’s dynamic labour needs, and replace it with a system where visas don’t tie anyone to a single employer. This would be better for workers, simpler for the Home Office to administer, and significantly cheaper for employers. The less ambitious version would be to implement safeguards to curb the power of sponsoring employers.[xiii] This included imposing fines and penalties for rule-breaking employers, giving workers 6 months (not the current 60 days) after the end of employment in which to find another sponsor, and instituting a Workplace Justice Visa to empower victims to report exploitation, without fear of losing their immigration status. All these measures are already in place, in some iteration, in Australia, Canada, and Ireland. Unfortunately, it is not what the UK government did.

The government learns the wrong lessons

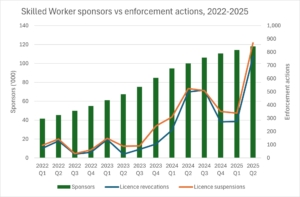

Faced with mounting evidence of exploitation, the Home Office improved due diligence at the point of licensing new sponsors, and radically increased actions against employers already on the list. Having started with a laissez faire approach, by 2024 the department was revoking hundreds more licences every quarter (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Licence suspensions and revocations, and total number of sponsors. Source: Home Office: Quarterly sponsorship transparency data. Last updated Q2 2025

The sad irony, however, is that with every story of successful immigration enforcement against employers, migrant workers were collateral damage. Once a business lost its licence, all workers tied to it risked having their visas curtailed. Officially, this meant that people were left with just 60 days to find a new sponsor. Unofficially, the Home Office gave some workers (particularly in the adult social care sector) more time. But this momentary leniency was no match for the structural barriers that stood in the way of re-employment. By the time migrant care workers were looking for new roles, indebted and with months of involuntary unemployment accumulating, few had the finances to take up driving lessons and purchase cars, to meet the requirements of employers.

Re-employment was also impeded by the fact that, despite the protests of industry leaders and unions, the government made hiring foreign workers increasingly expensive. Successive governments raised the minimum salary requirements and costs of compliance (though none applied any financial penalties to non-compliant sponsors). After the latest changes imposed by Labour, a small bona fide employer in the care sector who wishes to hire a migrant worker for three years needs to make an upfront payment of over £2,500 to the Home Office, up from £1,870 before.[xiv] Set to “wean businesses of migrant labour” at all costs, from July 2025, the government also banned recruitment for roles below RQF level 6 (undergraduate degree), and entirely ended the international recruitment of care workers under the Health and Care Worker visa.[xv]

Yet now, just like before, civil servants have had to pull the rabbit out of the hat; re-invent another contorted system that projects an image of strict border control, while quietly catering for business needs. In the same breath, the immigration white paper announced the exclusion of roles below graduate level from the list of jobs eligible for sponsorship, and the re-introduction of some of those roles onto a new Temporary Shortage List. Temporariness plays today the same political role that sponsorship played after Brexit. It is the sticking plaster that desperately tries to marry the two competing objectives of economic mobility and border control, but manages only to increase business uncertainty and prolong the misery of migrant workers.

What is at stake?

It feels like we have been here before. It is endlessly frustrating to observe how so many lives get caught in the crosshairs of political communications strategy, and how moderate policy decisions that could safeguard migrant workers get buried in the rush to appear ever tougher.

None of the thousands of migrant workers who were exploited by Home Office-approved visa sponsors were compensated – though their employers walked away freely. The thousands more who will continue to arrive on employer-sponsored visas face the same risks of exploitation, because they face the same radical power-imbalance. Most disappointingly, migrants who hoped that their sacrifice was not in vain were recently dealt a blow when, unexpectedly and without consultation, the government announced it will double the time to settlement, from the current 5 years to 10 years. That is another five years of precarious work, at the mercy of visa sponsors; five years of visa fees and yearly Immigration Health Surcharge payments; and five years of exclusion from social security.

Workers’ rights advocates will no doubt have gleaned the bitter irony of seeing a Labour government betray migrant workers so ruthlessly. There is more. The government has sacrificed the scope of the Employment Rights Bill, so that key provisions like the adoption of a single worker status are delayed. Journalists have also reported that government insiders were considering introducing Employment Tribunal fees – a tried and previously binned provision that would put justice out of reach for the poorest workers. Then there is everything the government is unknowingly sacrificing by going back to the politics of control: business and consumer confidence, which are both critical to growth; faith in progressive values, which are now rebranded as “patriotic progressivism”; and our community cohesion, which is increasingly splintered by the language of us and them.

We need to say no to this. At the Work Rights Centre, we have a small but fierce team of lawyers who empower migrant workers to take action against rogue employers. We use every win to expose the system that fosters exploitation, and raise awareness of the reforms needed to safeguard migrant workers. Everyone can join, whether it is contacting their MP to call out the harm the government is causing to migrant communities, or getting their union to campaign. Unite and the Royal College of Nursing have led the chorus of union voices who condemned the degrading treatment of sponsored workers, and asked for an immigration system that ends the toxic tie of employer sponsorship. Given the risks that lie ahead, it is time for these voices to get louder.

Dr. Dora-Olivia Vicol is an anthropologist and CEO of the Work Rights Centre, a charity that provides free employment and immigration legal advice, and that uses frontline intelligence to advocate for better protections for migrant and vulnerable workers.

[i] Marina Fernández-Reino and Ben Brindle, ‘Migrants in the UK Labour Market: An Overview’, Migration Observatory, 2024, https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migrants-in-the-uk-labour-market-an-overview/.

[ii] Fernández-Reino and Brindle, ‘Migrants in the UK Labour Market’.

[iii] Gino Spocchia, ‘RIBA Says Government’s Immigration Clampdown Risks 1.5m Homes Target’, The Architects’ Journal, 15 May 2025, https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/riba-says-governments-immigration-rhetoric-risks-1-5m-homes-target.

[iv] Aletha Adu and Aletha Adu Political correspondent, ‘Labour Axing Care Worker Visa Will Put Services at Risk, Say Unions and Care Leaders’, Society, The Guardian, 11 May 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/may/11/labour-axing-care-worker-visa-will-put-services-at-risk-say-unions-and-care-leaders.

[v] ‘Record Numbers of Visa Sponsor Licences Revoked for Rule Breaking’, GOV.UK, 2025, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/record-numbers-of-visa-sponsor-licences-revoked-for-rule-breaking.

[vi] ‘Prime Minister’s Statement on EU Negotiations: 24 December 2020’, GOV.UK, 24 December 2020, https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/prime-ministers-statement-on-eu-negotiations-24-december-2020.

[vii] Adis Sehic and Dora-Olivia Vicol, ‘The Systemic Drivers of Migrant Worker Exploitation in the UK’, Work Rights Centre, 2023, https://www.workrightscentre.org/news/report-the-systemic-drivers-of-migrant-worker-exploitation-in-the-uk.

[viii] Sehic and Vicol, ‘Report’.

[ix] Rosie Swash et al., ‘Rape and Sexual Harassment Reported by Foreign Care Workers across UK’, Global Development, The Guardian, 12 March 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2024/mar/12/health-care-worker-visas-abuses-exploitation-rape-sponsors-right-work-uk; ‘Migrant Carer “drowning” in Debt after £15k Visa Scam’, Cornwall, BBC News, 21 February 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-cornwall-68337205.

[x] ICIBI, ‘An Inspection of the Immigration System as It Relates to the Social Care Sector (August 2023 to November 2023)’, GOV.UK, 2024, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/an-inspection-of-the-immigration-system-as-it-relates-to-the-social-care-sector-august-2023-to-november-2023.

[xi] ‘Parliamentary Report Acknowledges Scale of Exploitation on the Skilled Worker Visa | Work Rights Centre’, accessed 3 October 2025, https://www.workrightscentre.org/publications/2025/parliamentary-report-acknowledges-scale-of-exploitation-on-the-skilled-worker-visa/.

[xii] Shanti Das, ‘Flawed UK Visa Scheme Led to “Horrific” Care Worker Abuse, Says Watchdog’, World News, The Guardian, 16 March 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/mar/16/flawed-uk-visa-scheme-led-to-horrific-care-worker-abuse-says-watchdog.

[xiii] ‘Safeguarding Sponsored Workers: A UK Workplace Justice Visa, and Other Proposals from a Six-Country Comparison | Work Rights Centre’, accessed 3 October 2025, https://www.workrightscentre.org/publications/2025/safeguarding-sponsored-workers-a-uk-workplace-justice-visa-and-other-proposals-from-a-six-country-comparison/.

[xiv] ‘No Match. Why Funding Rematching Hubs for Displaced Migrant Care Workers Is Not Enough to Tackle Exploitation | Work Rights Centre’, 10, accessed 3 October 2025, https://www.workrightscentre.org/publications/2025/no-match-why-funding-rematching-hubs-for-displaced-migrant-care-workers-is-not-enough-to-tackle-exploitation/.

[xv] ‘Latest Changes to the Immigration Rules: “A Sub-Optimal Way to Make Policy” | Work Rights Centre’, accessed 3 October 2025, https://www.workrightscentre.org/publications/2025/latest-changes-to-the-immigration-rules-a-sub-optimal-way-to-make-policy/.

Image credit: Steve Sharp via Unsplash