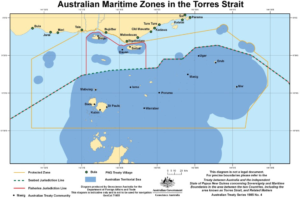

Figure 1. Australian Maritime Zones in the Torres Strait

The Torres Strait archipelago occupies a unique geographical and political position at the northeastern tip of Australia, forming a maritime border with Papua New Guinea since its independence from Australia in 1975. This small region, home to approximately 4,000 Torres Strait Islanders, is not just a geographical boundary between two nation states. It is a fluid borderland where work, identity and mobility are shaped by complex historical forces and contemporary governance arrangements that shape how Islanders navigate economic opportunity across multiple jurisdictions.

Understanding work in the Torres Strait requires examining how borders function not merely as lines of separation between nation states, but as a fluid and dynamic space that shapes labour patterns, economic choices and community formation. The map above communicates multiple borders and jurisdictions, including the Torres Strait Protected Zone negotiated in a 1985 treaty to enable residents of the northernmost islands and 13 coastal Papua New Guinean communities to move across the Seabed Jurisdiction Line without passports for traditional visits, fishing and trade. As a result, the border has been described as serving a dual function as both bridge and barrier.

The legal and governance complexity in international law in the Torres Strait is compounded by the distinct jurisdictional responsibilities of the federal government of Australia and those of the state of Queensland, and the rights established through the Native Title Act 1993 which acknowledged in Australian law the specific laws and customs of different Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups that preceded colonisation.

Importantly, then, viewing the Torres Strait solely through the lens of a fixed international border, in which the mobility of Islanders to the Australian mainland for work is understood as a practice of internal migration, would obscure the region’s deep history as a zone of mobility, trade and kinship connections. The contemporary borderland is not simply a space that mediates relative economic opportunities (and consequent relative disadvantages); it also demonstrates how a colonial border imposed on an historically fluid borderland continues to shape and mediate patterns of movement informed by obligation to family and community, belonging to place, and cultural and economic exchange, in ways that precede and exceed the imposition of state borders.

Moreover, in keeping with broader Indigenous philosophy, which emphasises the intersecting and overlapping nature of past, present and future, the future of work and migration in the region is firmly embedded in past and present structures and conditions. It is also the case that, in contrast to ill-informed perceptions of the sedentary nature of Indigenous cultures, the story of the Torres Strait was and will continue to be one of mobility.

The post-World War Two period marked a watershed moment for Torres Strait Islanders. The formation of the Torres Strait Light Infantry saw Islanders travelling to the mainland (and around the world), resulting in returning servicemen bringing back stories of new employment opportunities beyond the local pearling and fishing industries. In the context of Australia’s post-war migration programme to address labour shortages, Islanders, while not being migrants per se, nonetheless found growing employment opportunities on the mainland.

This post-war era represented the critical mass movement of Islanders from the Torres Strait to mainland Australia, setting in train the diaspora that today sees the great majority of Islanders living away from the Strait: Compared to a home population of approximately 4,000, more than 70,000 Torres Strait Islanders are now residing on mainland Australia.

In historical terms, it was a normal part of everyday Islander life in the Torres Straits to have movement between islands and wages withheld, regulated or otherwise subject to the permission of the local Protector, affecting the economic wellbeing of families and the community as a whole. By contrast, Torres Strait Islanders working on the mainland found themselves relatively ‘free’ from such government controls over their movements.

This everyday reality – in which life in the Islands meant continued restrictive government control, while migration offered relative freedom from such colonial administration – fundamentally shaped Islander mobility as both economic strategy and political protest. The mainland thus paradoxically offered greater autonomy than home islands despite Islanders simultaneously facing marginalisation and discrimination in ‘White Australia’, revealing how borderland mobility became entangled with assertions of Islander agency against multiple forms of constraint.

This created a distinctive borderland experience where movement and opportunity were shaped by complex governance arrangements operating across multiple scales. Islanders maintained language, kinship, cultural and economic ties both to Papua New Guinea in the north and to mainland Australia to the south, navigating economic opportunities while negotiating their sense of place and belonging on land other than their ancestral home. While Islanders moved south for mainland employment, the Torres Strait Treaty simultaneously maintained Papua New Guinean access to the Torres Strait fisheries, creating asymmetrical cross-border flows shaped by different economic conditions.

The opportunities on mainland Australia, however, resulted in the majority of Islander emigrants moving south rather than north, and this is reflected in the diaspora today. Furthermore, when Australia initiated processes to support the independence of Papua New Guinea, there was initially a proposal that the new state border be drawn through the middle of the Torres Straits, which would have resulted in some islands falling under Papua New Guinean jurisdiction and others under Australian. Islanders rejected this, leading a ‘Border No Change’ campaign that successfully resulted in the establishment of a shared maritime zone, resulting in more fluid treatment of the new state border, which reaches above the northernmost islands in the Torres Strait and by the 1990s was generating an estimated 4,000 crossings.

Biographical accounts of prominent Islanders like Eddie Koiki Mabo reveal that many did not view mainland migration as permanent resettlement or rejection of their culture and people. This pattern reflects what migration scholars recognise in other borderland contexts: mobility as a livelihood strategy that operates within, rather than against, commitments to place and community. Moreover, it is mobility that operates within and beyond the nation state reflecting the fluidity that has always been characteristic of the Torres Strait.

For Torres Strait Islanders, this mobility is not a matter of leaving or staying, but reflects the negotiation of multiple political and economic environments that overlap in the region. This results in mobilities that navigate not just between geographical destinations, but negotiate between governance systems (local, state, federal, international), distinct economies (customary and commercial, domestic and international) and dynamic relations that are ever changing between homeland and diaspora Islander communities. This demonstrates how the region reflects ongoing negotiations across multiple domains, between tradition and opportunity, home and away, giving shape and form to the contemporary diaspora.

Torres Strait Islander mobility has never been a simple story of departure. While today’s pressures are different including a severe shortage of housing in Island communities, climate-induced mobility shaped by rising seas and shifting livelihoods, and education pathways that often require young people to spend formative years away from home, the underlying logic remains familiar.

Movement continues to be a strategic response to structural constraints rather than a break from kin, communities or culture. What is shifting, however, is the fluidity of return. Digital connectivity, cheaper air travel and stronger community governance now make it possible for Islanders to circulate more frequently between the mainland and the Torres Strait in ways that were far less accessible in previous decades. The borderland remains a living space of negotiation over ontological connection and belonging to country, community, ancestors and future generations, where mobility continues to shape how Torres Strait Islanders imagine and build their futures.

Adrian Little is Professor of Political Theory at the University of Melbourne. His expertise lies in social and political theory, and he has written extensively on conflict and democratic theory, Indigenous politics and the politics of Northern Ireland. With his co-authors, he is a Chief Investigator on the ARC Indigenous Discovery project on Navigating the Tides of Change: A Study of Political Action and Change in the Torres Strait.

Sana Nakata is a Torres Strait Islander scholar trained in law and political theory at James Cook University. She currently holds an ARC DAATSIA Fellowship (2025–2030) for the project Navigating the Tides of Change: A Study of Political Action and Change in the Torres Strait with Professors Adrian Little, Felecia Watkin Lui and Martin Nakata.

Felecia Watkin Lui is a Torres Strait Islander academic with connections to Erub, Mabuiag and Badu. She leads research focused on the intersection of health and the environment, and currently holds an ARC Future Fellowship (2026–2030) examining Torres Strait Islander mobility amid climate change. She serves as Chief Investigator on multiple national research projects, including Navigating the Tides of Change: A Study of Political Action and Change in the Torres Strait with her co-authors.

Image credit: Stacie Ong via Unsplash