Political debate on immigration currently includes very little forward thinking: the current government is desperately trying to make its policies on asylum seekers work; and both parties have pledged to bring down net migration, which has recently been at record levels. Immigration looks like being the hottest topic in the parties’ 2024 election campaigns.

But immigration isn’t a short-term election issue. It is integral to how the UK delivers its economic goals and runs key services and industries including health and social care, food production and construction. What will happen to levels of migration in the coming months and how should the next government, which is likely to be Labour-led, respond? What does the public think about these challenges and how should their views be considered?

Net migration has been unusually high in the past two years. The Office for National Statistics estimates that net migration to the UK was 745,000 in 2022. This was more than four times the pre-pandemic level in 2019. The recovery period, from January 2021 onwards, not only saw an increase in migration for work, and for study. It was also boosted by high numbers arriving via humanitarian routes.

Both Labour and Conservative politicians have argued that immigration is ‘out of control’, despite the figures very much reflecting decisions to allow entry through specific visa routes. Both Conservatives and Labour have pledged to reduce net migration. The government reacted with changes to the visa system, raising the salary threshold for skills visas and placing restrictions on the right to bring dependants. These changes, along with a fall-off in numbers arriving from Hong Kong and Ukraine, will mean that the start of a new government will coincide with lower net migration figures. While this might be seen as to its advantage, the reductions it reflects will have been achieved through exacerbating shortages in some key sectors resulting in pressure from representatives of businesses and services to relax restrictions.

The need for employers to train British workers to reduce their reliance on migrants has been a consistent message from the Labour Party: In 2013 Ed Miliband made an election pledge to force employers to train a local worker for every foreign recruit, to upskill the next generation. Ten years on, the party is arguing for investment in young people ‘first and foremost’, rather than immigration, to fill labour shortages. This would make sense if migrants were substitutes for training, but the evidence consistently shows that they aren’t. A recent survey by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development finds that employers who recruit via work visas are more likely than those who do not to be investing in recruitment, training and upskilling of UK staff: this includes hiring apprentices, UK graduates, school and further education college leavers. They are also more likely to have recruited parent returners, older workers and to have hired from disadvantaged groups.

It is pay and working conditions, rather than reluctance to train, that explains why some sectors rely on migrants to fill vacancies: Recruits to most roles in hospitality, social care, agriculture and food and drink production require on-the-job training and practice rather than qualifications. Pay, flexible hours and the nature of the work make these sectors unattractive to British workers. For these reasons, it has been necessary to introduce bespoke visa schemes for social care and for agriculture. Historically these also existed for food production and hospitality.

A government that wants to reduce reliance on migrants in some sectors will need to increase in-work benefits or reduce taxation at the lower pay end substantially. For social care a more root-and-branch approach is needed to address low pay, poor working conditions and limited opportunities for advancement: Care worker recruitment accounts for more than a third (37 per cent) of all work visas. The Labour Party has not yet made a commitment to carry out much-needed reform.

Along with thinking that employers want more immigration, politicians often believe that the public wants less. Yet research findings show attitudes towards migration for work, and more generally, have become more positive in recent years. The immigration tracker survey carried out by British Future and Ipsos has found that this becomes most apparent when people are asked about specific occupations.

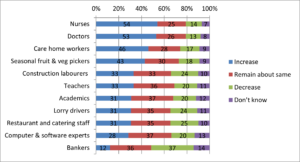

The latest survey in August 2023 found almost eight in ten people in favour of increasing the number of migrant nurses and doctors, or keeping them the same. Almost three-quarters support this approach for social care and seasonal agricultural workers. A majority would also support at least continuing current numbers of migrant recruits in construction, teaching, universities, road haulage, hospitality and IT:

In 2022 the survey asked those who said their attitudes had become more positive why this was. More than four in ten (42 per cent) who said they were more positive said discussions about the role of migrants since the referendum had highlighted the contribution of migrants to the UK. The pandemic also played a role in this shift, with more than half saying it had made them more aware of the role of migrants in key services such as health and social care.

Labour and skills shortages contributed to slow recovery from the pandemic dip, with fewer migrants to fill gaps and older people exiting the jobs market early. In this period concerns other than migration become more prominent, with the economy frequently higher up the list. The public’s mind was focused on how the economy, and individual lives, could return to normal.

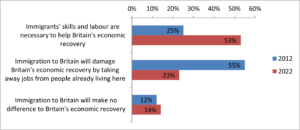

In this context, a survey question asked by British Future in 2012 and again in 2022 found 53 per cent in agreement with the statement ‘Immigrants’ skills and labour are necessary to help Britain’s economic recovery’ and 23 per cent with the alternative ‘Immigration to Britain will damage Britain’s economic recovery by taking away jobs from people already living here’. As the table shows, in the space of ten years immigration switched in the public’s mind from being an economic problem to part of the solution to the challenge of economic recovery.

These trends in public attitudes suggest that a new government should not need to feel torn between achieving economic goals and addressing public concerns on immigration for work. It has scope to put in place policies to ensure that businesses and services are able to recruit migrants to fill gaps, while offering opportunities for everyone else.

At the same time the public is likely to strongly support policies to improve training opportunities for young people, higher pay for low-skilled workers and a better-resourced social care system. But these policies should be pursued alongside policies for migration and for migrants, not instead or in opposition to them.

Dr Heather Rolfe is Director of Research at British Future.

Image credit Orva studio via Unsplash