Over the past decades, Canada has encouraged international mobility and the use of temporary migrant workers to overcome quantitative and qualitative labour shortages. However, the country was put on the spot last year by a United Nations Special Rapporteur who provided unfavourable findings regarding certain work and employment management practices that placed these workers in a highly vulnerable position. His main criticism lies with the employer-specific work permit, which stems from the programme governing the arrival, stay and working conditions of migrant workers – the temporary foreign workers (TFW) programme – and which, according to the rapporteur, constitutes a breeding ground for modern slavery. Under the Canadian constitution, legislative jurisdiction over immigration and migration is shared between the federal government and the ten provinces plus three territories. However, employers from specific provinces have endeavoured to influence regulatory amendments in their favour, decrying lasting labour shortages and a need for all levels of government to enable rather than constrain international recruitment processes.

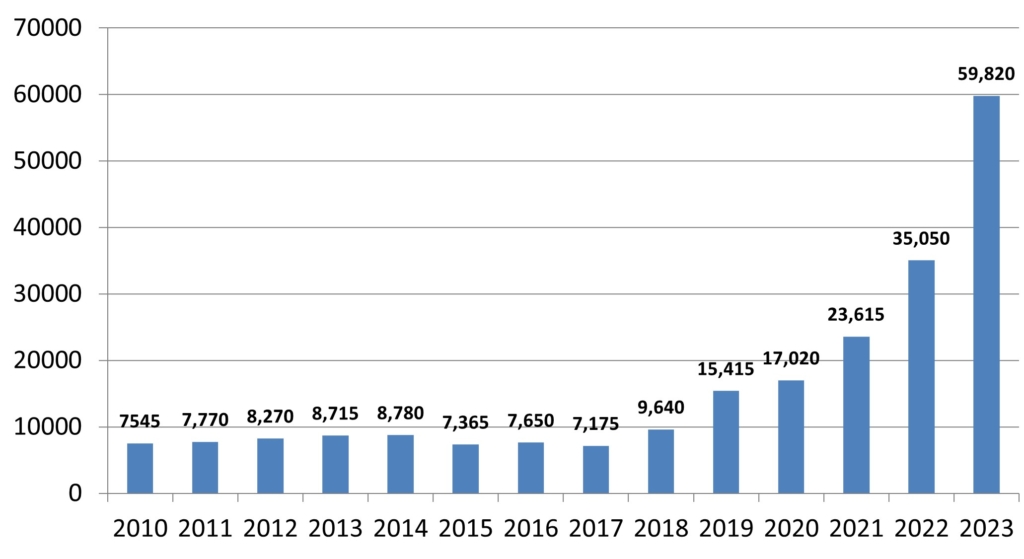

In a 2024 piece, we examined the specific case of Quebec amid the Canadian context, which clearly illustrates the issues and dynamics at play, following the unprecedented growth of temporary migration in the province (see Chart 1).

Chart 1: Number of temporary foreign worker work permit holders in Quebec (2010–2023*)

*As of 31 December 2024

Source: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2024.

Three main elements emerged from our recent work. First, employers seem to be path-dependent and resort to the same labour markets outside Canada to seek new candidates and fill recurring labour needs. At a certain point, employers notice a new country with a labour market eligible to address their labour shortage and, in successive years, repeat their demand for labour from this destination. Illustratively, prior to the turn of 2010, there was an employer focus on the labour market in Mauritius, among other Francophone countries, and this led to the recurrent recruitment of workers from the island state to fill both skilled and unskilled positions in Canada. Mauritians have arrived in groups to fill jobs, for instance, in industrial slaughterhouses and other food-processing plants in the Quebec province. The experience of these migrant workers is described in the documentary Terre promise (Promised Land), directed jointly by Catherine Lemercier and Blandine Emilien. In this industry-specific context, Mauritians’ French proficiency and education qualified them for these jobs, which require the capacity to hear task instructions in French in a noisy work environment. It was also assumed that Mauritian workers would be able to adjust to a Francophone culture in both their workplace and private lives. Overall, however, the labour pool into which Quebec employers tap to fill their positions is composed of workers from a range of countries, including Guatemala, Mexico, the Philippines and France.

Second, we observed the rapidly and constantly changing regulatory system that frames temporary migration programmes in Canada and seems to indicate a greater politicisation of the issue. Just as in many countries around the world, political and public debates revolve around the country’s and provinces’ ability to integrate more permanent and temporary (im)migrants. These debates led the Quebec government to tighten rules and criteria to reduce the use of temporary migrant workers. Such a tightening is far from unanimous among labour market actors. Politicisation of the issue of immigration, whether temporary or not, is likely to continue during the federal election campaign, now underway. In light of President Trump’s threat to impose tariffs on Canadian imports, governments may choose to ‘walk through the wet paint’ and relax these restrictions. A sign of this turnaround is the recent announcement that in Quebec an employer who has been convicted of breaching labour standards, violating health and safety laws or discriminating against this group of workers will be able to resume hiring temporary workers more quickly. The period of ineligibility for the programme would then be reduced from two years to six months. Despite the multiplying activist struggles that are opposing the persistence of employer-specific permit delivery, these recent pro-employer measures taken by the Quebec government predict a continued reliance on a temporary migrant labour pool and the ensuing issues facing migrant workers themselves once they are hired.

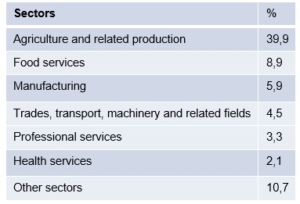

Third, we understand that migrant individuals settling in Canada through work-related migration pathways face varied realities and cannot be seen as a homogenous population. While they are mostly classified as skilled and non-skilled labourers, within these two groups we find differentiated sub-categories (see Chart 2). So far, Canadian institutions have not clearly addressed the realities experienced by groups of workers placed in different occupations and social environments. As a result, unions and other social actors who attempt to promote decent work and decent migration in favour of temporary migrant workers in Canada face difficulties adjusting their support for these workers’ distinct needs. In varying degrees, and across industries, workers and their representatives are confronted by issues pertaining to francisation, the adaptation of employment conditions, health and safety problems, psychological abuse, exploitation, discrimination and racism, challenges regarding integration into union representation and psychosocial risks due to isolation and migration-related adaptation requirements. Some of these issues are addressed within the scope of collective bargaining for temporary migrant workers who are unionised, while some categories of workers, such as those involved in seasonal agricultural work, do not benefit from such social protection and dialogue.

Chart 2: Distribution of TFWP work permit holders by economic sector in Quebec in 2023

Source: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2024

Labour shortage has been experienced in the province of Quebec in both high- and low-wage occupations. That said, the arrival of workers to fill less skilled positions in industries such as food processing (see Chart 2: Manufacturing) and agriculture (see Chart 2: Agriculture and related production) has increased in recent years. This has exacerbated some of the tensions and contradictions that their temporary status implies: while these workers are hired within the principle of circular migration, with latent expectations from governments of their returning to their countries, they aspire to a better and permanent life in Canada. The case of temporary migrant workers hired in food processing is particularly interesting: it has demonstrated some of the psychosocial challenges facing temporary migrant workers involved in hard and dirty work, while living away from their families, who were not able to join them early in their migration time. Our studies find that workers feel constrained by their employer-specific work permits in their attempt to find relative stability in their personal and non-work lives. New research by Canadian scholars reminds us of the impact of migration backlogs on workers’ mental health due to anxiety triggered by uncertainty regarding their migration status. The last and most striking contradiction and irony, denounced by several social actors, including unions, is the use of temporary workers to meet labour needs. These are likely to be ‘permanent temporary workers’ who, in many cases, would like to settle in communities that would only be too happy to welcome them on a permanent basis.

Certainly, the temporary migration phenomenon has opened a Pandora’s box within Canadian institutions. Social actors such as unions and province-based activists are concerned by workers’ fates amid the restrictions that temporary migration status and the employer-specific work permit situation imply for workers’ security and wellbeing. In our research, we were able to hear concerns from unions and activists operating within non-profit organisations such as the Immigrant Workers Center (IWC-CTI, see also the documentary Promised Land) regarding their imperative to better understand migrant workers’ distinct realities, and develop more sustainable mechanisms that will help bridge workers’ needs across the Quebec labour pool to avoid migrant workers’ exclusion from decent protection. The abolition of the closed permit could certainly reduce the vulnerability of TFWs to abuse and exploitation. However, it would not address the fundamental problem facing businesses, which is to rely on a production model that has great difficulty recruiting Canadian workers, but which only survives because it is fuelled by a flexible migrant workforce.

Patrice Jalette is Professor in Industrial Relations at Université de Montréal, and a co-researcher at the Inter-University Research Center on Globalization and Work (CRIMT), Montreal, Canada.

Blandine Emilien is a lecturer in Human Resource Management and the Future of Work at the University of Bristol Business School, UK and a co-researcher at the Inter-University Research Center on Globalization and Work (CRIMT), Montreal, Canada. She co-directed the short documentary, Terre Promise (Promised Land) with Catherine Lemercier. The documentary is available on the CRIMT website.

Image credit: Adèle Beausoleil via Unsplash