Bordering on criminal: Legitimising unlawful extraction

The origins of the word ‘border’, which can be traced to a shield’s edge (bordeure) or the planks (bord/board) that formed the side of a ship, resonate along the banks of the Tapajós River in the Munduruku territory of Brazil. The edge between the Munduruku ancestral lands and the worlds of non-indigenous settlers has been travelled, transgressed and contested since the first colonial boats navigated the Amazon. It could be argued that the historical treatment of the Amazon as terra nullius, devoid of people with distinct histories, territories and parity of rights, is reproduced in enduring Western imaginaries of pristine forests, and top-down developmentalist strategies aligned to cartesian presentation of space and linear conceptions of time and progress.

In this context, the material borders that delineate the boundaries of the officially recognised indigenous territories in Brazil represent for the inhabitants a spatial and temporal horizon, the protection of which affords the reproduction of collective life, work and meaning within the forest. This article contends that for land grabbers, wildcat miners, state institutions and commercial organisations alike, these borders represent a legislative and geographical obstacle to be reworked, reinterpreted and overcome in preparation for further commercialisation of land and labour. This article explores the outworkings of this in relation to the border between Munduruku lands and Crepori National Forest, and the illegal gold and ‘regulated’ timber extraction therein.

Asymmetrical temporalities on the edge of two worlds: The case of Crepori

It was amid the repression of Brazil’s military regime that the Munduruku began expeditions towards territorial defence of their sovereignty in the 1970s. This process of territorial control in the face of ongoing government omission, which became enunciated as self-demarcation from 2014 onwards, involved successive teams monitoring and confronting invaders, mapping and demarcating their boundaries and containing land-related violence. The actions led to 2.38 million hectares being designated for their exclusive use in 2004.

The late 20th century saw new constitutional changes in Brazil that guarantee lands and rights for Amazonian communities. It is difficult not to conclude, as does Robert Nichols however, that these territorial borders – ostensibly drawn to protect distinctive and indigenous social, economic and political activities – represent conversely ‘an unincorporated horizon’ for the relentless pressures of capitalist expansion. As detailed below, the slow and incomplete process of officially demarcating these lands – there are at least 850 indigenous lands that have not yet been defined – makes them vulnerable to illegal incursions, and contrasts sharply with the rapidly introduced bills that seek to weaken the existing legal protections offered by these borders.

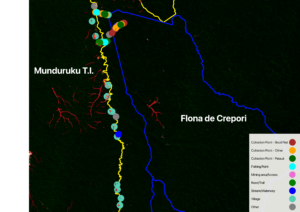

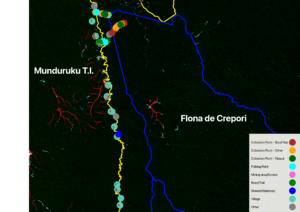

The Crepori National Forest, or ‘Flona’, with 740,661 hectares, was created in 2006, bordering the Munduruku lands (TI Munduruku), but incorporating areas historically and contemporarily used by the Munduruku people, who were not consulted, in violation of ILO 169 (which requires governments to involve indigenous and tribal peoples in relevant legislation and projects that will affect them) and the Brazilian constitution. A ‘Flona’ is a conservation area, but with a specific designation that allows the commercial extraction of resources within its boundaries. The denial of the existence of indigenous occupation, therefore, paved the way for the auctioning off of parts of the forest. Figure 1 illustrates that neither the boundaries of indigenous lands nor the conservation area were effective in preventing illegal gold mining and deforestation.

Figure 1 Map showing border (in yellow) between the Munduruku Lands (TI) and Crepori Flona, and the places of traditional use (open circles) by Munduruku. These extend through to the designated Flona and within the licensed zone for commercial logging concession (in blue). Areas of illegal mining in both the indigenous land and national park, 2001-2021, are shown in dark red.

Figure 1 Map showing border (in yellow) between the Munduruku Lands (TI) and Crepori Flona, and the places of traditional use (open circles) by Munduruku. These extend through to the designated Flona and within the licensed zone for commercial logging concession (in blue). Areas of illegal mining in both the indigenous land and national park, 2001-2021, are shown in dark red.

A formal complaint in 2014 by the Munduruku paused the planned operations:

Our activities of fishing, hunting, harvesting fruits, straw and vines are prohibited, in an area that is our traditional territory […] where the federal government created the Flona without consulting our people.

The irony for the original residents is that although the logging concession was temporarily suspended, the Supreme Court decision that recognised the ‘suffering from illegal activity’ and ‘predatory’ deforestation led not to a cancellation of the logging contracts but rather the opposite: Regular logging would be permitted as it would help tackle the illegal extraction of timber and the wildcat gold mining activities.

Since the licensing for regulated logging became operational in August 2023, the enclosure of forest for logging, the noise of machinery and siltation of rivers has forced locals to go further to hunt, fish and gather fruit. Most notably, however, along the paths through the forest, young men still working as illegal miners talked openly of friendly relations with the employees of the timber company that was awarded the contract.

The drone image (Figure 2) shows the alarming extent of illegal mining, visible as the ponds of deforested areas to the left of the picture, that has been facilitated by the principal road infrastructure (running south to north in the image) built by the logging company. Figure 3 qualifies the local accounts of forest loss and persistent illegal mining since the timber concessions came into operation.

Figure 2 A drone image of illegal gold mining sites adjacent to the ‘official’ road of the timber company, August 2025; Image courtesy of Da’uk Munduruku audio visual collective

Figure 3 Map showing recent forest loss (2022–2024) from illegal mining (in light blue) within the indigenous lands and Flona. Forest loss between 2001 and 2021 is shown in dark red.

This situation is a typically unruly frontier encounter. Currently, mining is illegal in indigenous territories, meaning that the labour undertaken by poorly paid workers and most often organised by unseen actors is by necessity clandestine, precarious, undocumented and, because of its geographical remoteness, ‘slave-like’ (under the Brazilian legal definition). Although condemned by the Munduruku leaders, this activity has been co-opting young, indigenous men into capital-waged labour relations leading to internal conflicts that are a manifestation of the broader tensions between the protection and capitalisation of the forest resources.

An increase in logging concessions continues to be pushed as a tool for forest conservation as part of a broader belief in regulation through private property; yet indigenous groups have long argued that effective, statutory protection of their territorial borders is a sufficient guarantee of forest preservation. What they now face is the contrary: Federal courts are currently debating laws that would make legal wildcat mining in indigenous territories by non-indigenous peoples (Bill 1331/2022) and would for the first time allow transnational corporate mining in these lands (Bill 6050/2022). Furthermore, the authority to demarcate indigenous lands would be transferred from government to a National Congress (PEC 59/2023) dominated by a pro-agribusiness lobby that has already stated it would paralyse the demarcation of indigenous lands. The evidence presented here is of a symbiotic rather than conflictual relationship between illicit and ‘regularised’ extraction, whereby new ‘legal’ infrastructures facilitate rather than tackle the transgression of ostensibly protective borders, with grave implications for the sovereignty and livelihoods of indigenous and traditional communities and the ecosystems of which they are part.

The Amazon’s centrality to overlapping, converging and conflicting strategies for carbon capture, carbon trading, timber and mineral extraction at a global scale means that the regulatory challenges presented here are also of a transboundary nature. Not only are some 3,600 mining applications scattered across the basin, but the UK government is among those investing in the region under the premise that well-defined property rights will help tackle illicit land grabs and invasion. This liberal market-based belief has already underpinned the UK’s partnership with Brazil to section some 1.3 million hectares of the globe’s most important biome to timber extraction, while planning a further 5 million hectares until 2030.

The institutional enthusiasm and justification for these transborder strategies and transactions rely on the continued imposition of a linear temporal framework and steeply hierarchical policy agenda that determines to transform space and, importantly, social relations at the frontier. A logic that seeks to bring into line those whose resistance has historically been translated as a barrier to progress is thus sustained by the developmentalist agenda for the Amazon. Although this may be accompanied by a discourse that departs from previous colonial and military periods, the protests of the Munduruku that temporarily shut down the Climate Change Conference of Parties (COP 30) in Brazil’s Amazon manifest that alternate visions, social and ecological relations persist within their territorial borders that could provide for social and political possibilities beyond them.

Rosamaria Loures is a doctoral candidate in Social Anthropology at the University of Brasília (UnB). She holds a master’s degree in Environmental Sciences from the Federal University of Western Pará (UFOPA), and works as an advisor to the Munduruku Wakoborũn Women’s Association (since 2018) and the Munduruku Ipereğ Ayũ Movement (since 2012).

Brian Garvey is a researcher at the Department of Work, Employment and Organisation at the University of Strathclyde. His current research investigates local and global tensions related to labour, land use and the commodification of natural resources. He is a co-founder of the Centre for the Political Economy of Labour.

Steven Owens is a researcher specialising in geospatial data for corporate accountability with a focus on supply chain transparency, working in collaboration with Indigenous communities.

Mauricio Torres holds a Masters and PhD in Human Geography from the University of São Paulo. He is Professor at the Institute of Amazonian Agriculture (INEAF) and at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), and Coordinator of the Decentralized Execution Agreement between the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples (MPI) and the Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

Deise Cristina Lima de Oliveira holds a degree in Rural Development from the Federal University of Pará (UFPA) and is a master’s student in the Amazonian Agriculture Program at UFPA, where she conducts research in the area of territorial conflicts and the rights of traditional peoples and communities. Currently, she is a technical advisor to the Wakoborũn Association and the Ipereg Ayũ Movement.

Ana Carolina Alfinito holds a law degree from USP and a doctorate in political sociology from the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies. She is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Amazonian Agricultures of the Federal University of Pará (INEAF/UFPA) and a consultant for the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples (MPI).

Hugo Gravina Affonso is a geographer and holds a PhD in Family Farming and Sustainable Development from the Federal University of Pará. He is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Amazonian Agriculture (INEAF/UFPA).

Bárbara Wanderley holds a bachelor’s degree in Geography from the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE) and a master’s degree in Geography from the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR). Currently, she is a doctoral candidate in Philosophy at the University of Strathclyde, where she is developing interdisciplinary research articulating philosophy and socioenvironmental conflicts.

Image credit: Mirna Wabi-Sabi via Unsplash